Pavia Royal Town

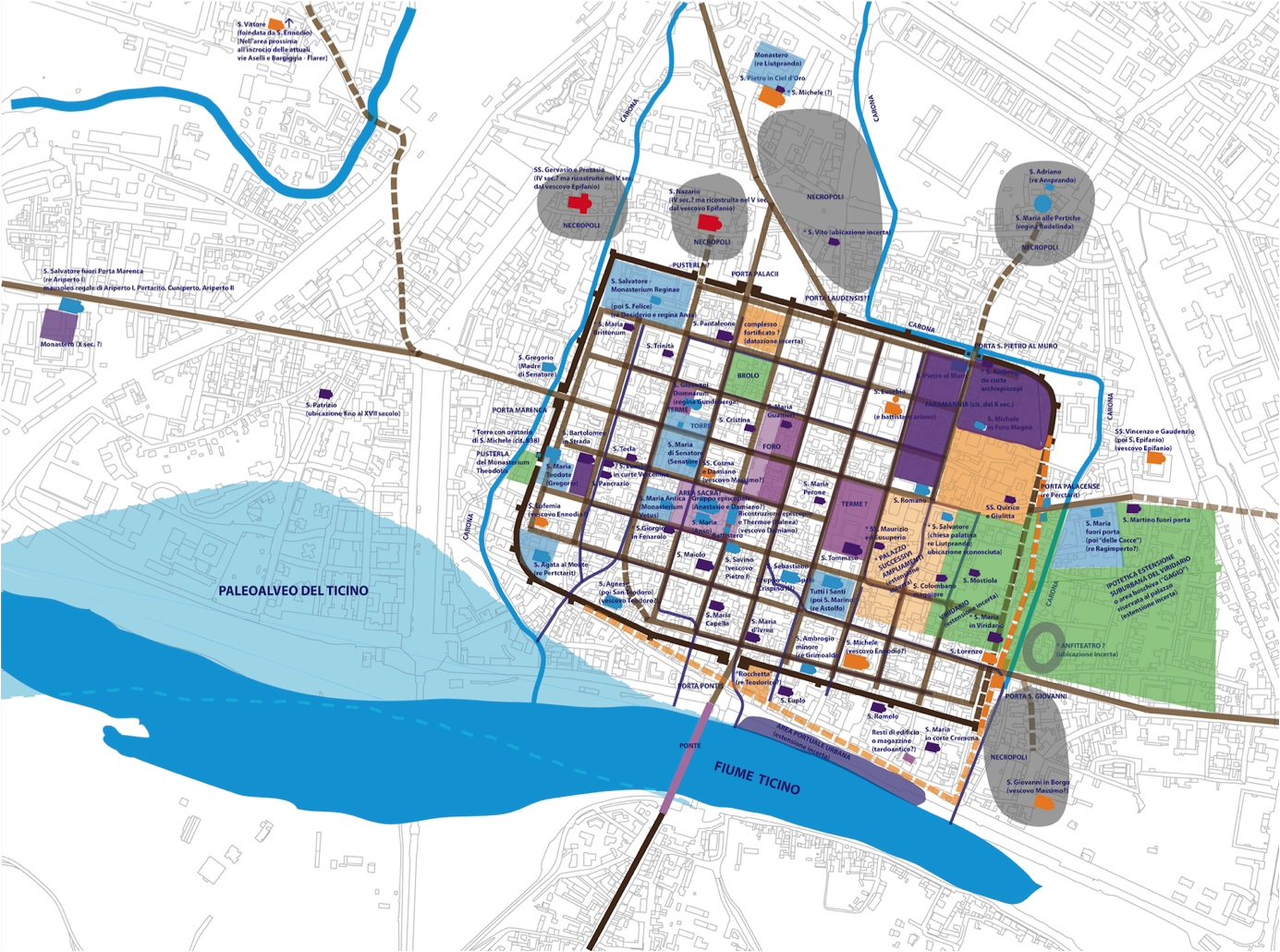

Imperial Abbeys in PaviaPAVIA IN THE ROMAN AGE (3th c.)

The first populations on the banks of the Ticino river came from the Gallic region; they choose this location because of the easy water communications. Pavia was then founded by the Romans in the 1st c. B.C. and was called Ticinum from the name of the river on the left bank of which it was built and developed over the centuries. Pavia was built on a flatted ground with square blocks ( ten in the East-West direction and six or seven in the North-South one). The “cardo maximus” road corresponded to the current Strada Nuova up to the Roman bridge while the “decumanum maximum” road corresponded to Corso Cavour-Corso Mazzini connecting two town gates. The light South East-North West slope was exploited when designing the Roman sewage system ending at the South-East corner of the town, therefore preserving the river crossing the town from water pollution.

PAVIA IN THE FIRST CENTURIES OF THE CHRISTIAN ERA

Originally Pavia was important as a military site because of the easy access to water communications up to the Adriatic Sea and because of its defence structures. Military events reported are, for instance, the defeat of general Stilicone in 408 and the sack of Rome in 410. In 476 Oreste, pressed by Odoacre, took refuge just in Ticinum. Just in that year Odoacre deposed the young Romolo Augustolo emperor and sent the imperial signs to Costantinopoli, recognizing the authority of the Eastern Roman emperor. That was the end of the Western Roman Empire and the following times were characterized by diversity and continuity at the same time.

Since the 4th c prominent figures in culture, at least religious, are reported. For example, it is known that in 325 Saint Martin, born in Pannonia from a Roman officer, came to Ticinum as a child following his father, and had his first education here according to the tradition of the time.

PAVIA AT THE AGE OF GOTHS

The late Roman legal, administrative, fiscal and military systems survived up to the Greek-Gothic war. Then Teodorico renovated them by building and repairing baths, walls theatre and palace of the town. The Western “empire” did not exist any more because the territory was under the control of the army of Ostrogoti. Nevertheless, Teodorico wished to cooperate with the previous tradition, thanks to the cultural support of Severino Boezio, al least up to 525. In his last years however, Teodorico, who was afraid of the policy of Giustino against Arians, left the solidarity with the pope and the Roman cultural elite, and sentenced Boezio himself to death.This cultural elite was confimed at the time of bishops Epifanio (438-496) and Ennodio (473-521) when, in 493, Teodorico moved his palace from Milano to Pavia, and the latter became a capital together with Verona and Ravenna. If Pavia became a royal town, this was due to its new specific cultural identity expressed also monuments that now. We can only imagine. Here are the roots of the obscure history of the origin of San Pietro in ciel d’oro, where the tomb of Boezio was located, we do not know exactly when.

Since 540 Pavia became the permanent capital of the kingdom of Ostrogoti, stable site of the court, of the royal treasure as well as of the mint. This happened after the Greek-Gothic war (535-553) by which Giustiniano tried to conquer Italy, when Roma and Ravenna were conquered by the imperial army and Milano was besieged by the Goths for having hosted a Byzantine garrison.

PAVIA AT THE TIME OF LOMBARDS, (7TH C.)

Some decades passed after the arrival of Lombards in Italy in 568 and their conquest of Pavia in 572 before the town became their only political capital in 625. Many building were erected in Pavia and from the 7th and the 12th c. Pavia was the main site of councils and synods . The town flourished particularly under king Liutprando. As concerns San Pietro in ciel d’oro documents suggest that, when in the years 721-725 the body of Saint Augustine was translated from Sardinia to Pavia, the king established a monastery attached to the church of San Pietro, located out of the Northern walls along the ancient road to Mediolanum. The body of king Liutprando was buried in the same church. To some extent a similar destiny occurred to the San Salvatore monastery, located out of the Western walls of the town near “Porta Marenga”. Probably in the same place of an ancient Lombard cemetery, the church of San Salvatore was founded in the second half of the 7th c. by Lombard king Ariperto I (653-661), It was dedicated to San Salvatore as a mark of “ the end of the Arian domination in Pavia with bishop Anastasio” and of “ the cancellation of Arianism as the official religion of Lombard people”.

PAVIA AT THE TIME OF LOMBARDS, (8TH C.)

Hosting the tombs of Ariperto I and then of his successors Pertarito, Cuniperto and Ariperto II and probably of others, the building of San Salvatore became a Royal mausoleum. For this reason it is not excluded that in San Salvatore one can still find the bones of the Lombard kings who were at the origin of its history. The stone with the inscription of king Cuniperto, in fact, most probably was laid on the tomb of the king in the Lombard church, was then transferred in the rebuilt one under the Ottoni’s , survived in the 15th c. when the church was totally rebuilt, was then reused in the little wall of the monastery, then was placed on the right wall of the church, at the beginning of the 19th c. was included in the Malaspina collection and finally came to the Musei Civici in the Visconti Castle where it is currently located. The complex of San Salvatore is the unique case among the still existing Lombard churches with tombs that preserves in situ materials of a monument of royal kings in the ancient capital of the kingdom.

PAVIA IN THE CAROLINGIAN AND OTTONIAN AGE

In 774 Charles the great conquered Pavia and declared himself King of Franks and Lombards; his purpose of maintaining continuity and diversity at the same time is evident. The policy of Charles the Great aimed at shaping a Christian empire which had to be strong militarily but also culturally and religiously; for this purpose he sent Frank bishops and paid attention to the life of religious people. Emperor Lotario, king of Italy from 822 to 850, paid attention to schools when in May 825, from Corteolona he issued his Capitolare, by means of which he prescribed that students from Milano, Brescia, Lodi,, Bergamo, Novara, Vercelli, Tortona, Acqui, Genova, Asti, and Como had to attend the lectures delivered by Dungallo teaching in San Pietro in ciel d’oro. Under him in 830 the royal court moved to Pavia from Milano that was preferred by Charles the great. It is not known exactly when the monastery attached to the church of San Salvatore was founded even if documents prove that in the second half of the 10th c. Empress Adelaide ( a.931-999) promoted the restructuring of the monastery and called San Maiolo, abbot of Cluny to reform it. With Ottone II, son of Adelaide, emperor from 973 to 983, Pavia became and became the stable site of the court first with queen Adelaide and then with the wife of Ottone II Teofano. Queens, like also in the Carolingian age, were devoted to the main town of the kingdom of Italy and became the stable site of the court first for queen Adelaide and then for the wife of Ottone II Teofano. Queens, like already in the Carolingian age, were devoted to the preservation of the memory of the dynasty by the foundation of monasteries. In this context the foundation of the San Salvatore monastery by Adeaide is placed. San Pietro in ciel d’oro, instead, became the site of an important scriptorium and was the destination of pilgrimages, stimulated by the royal and then imperial court, to the important burials. It was also the temporary residence of the court itself after 1024 when the ancient Palatium intra moenia, which was the residence of Teodorico, of the Lombard kings as well as of the Carolingian and Ottonian kings and emperors up to Enrico II, was destroyed. Like in the case of San Pietro in ciel d’oro, the great initial attention paid to San Salvatore by kings and emperors, made it as one of the sites of the court at the beginning of the 11th c and probably also in the 12th c.

A number of properties spread in a wide territory was granted to the monastery and important was its continuity as an institution with its architecture from the royal Lombard foundation as the dynasty mausoleum of burials, to the Ottonian refoundation as one of the main ecclesiastic institution of the empire, and to the age of Viscontis when it became one of the centres for the recovery of the royal Lombard origin by the Viscontis who proclaimed themselves the heirs of the Lombard kings. The monastery got new life when it moved under the congregation of Santa Giustina in Padua at the middle of the 14th c. and remained important up to the end of the 18th c.

FOUNDATION OF MONASTERIES

Two extra moenia monasteries for monks can be definitely called imperial monasteries because they included buildings as residences for emperors who stayed there after that the Palatium, centre of the town government, was destroyed in 1024 by the inhabitants of Pavia struggling against the imperial power. They are the monasteries of San Pietro in ciel d’oro and San Salvatore, located North and West of the town walls respectively.

Video-rendering of Pavia before the 16th c. (realized in the CVM Laboratory of the University of Pavia, courtesy of Virginio Cantoni, Director)

SAN SALVATORE

San Salvatore – Benedictine abbey rebuilt in the second half of the 15th c.

SAN PIETRO IN CIEL D'ORO

San Pietro in ciel d’oro – Romanesque Basilica rebuilt between 11th and 12th c.

MONASTERY OF SAN SALVATORE

Monastery of San Salvatore.

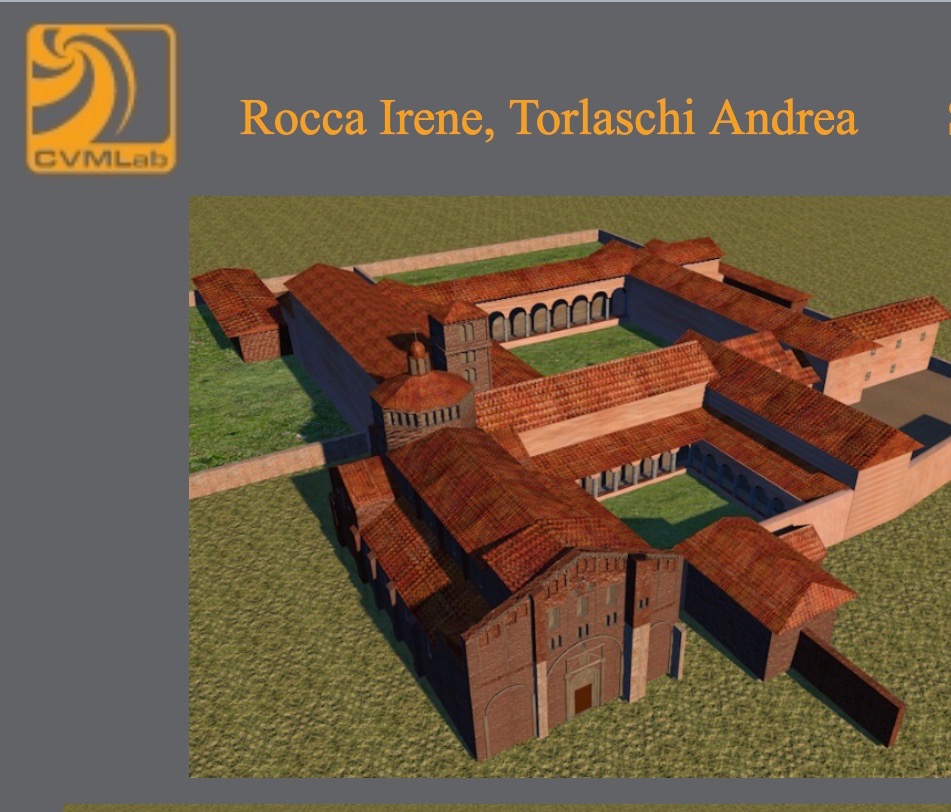

3D rendering of the Basilica of San Salvatore and San Mauro with the attached cloisters (realized in the CVM Laboratory of the University of Pavia, courtesy of Virginio Cantoni, Director).

MONASTERY OF SAN PIETRO IN CIEL D’ORO

Monastery of San Pietro in ciel d’oro. 3D representation of the Romanesque Basilica of San Pietro in ciel d’oro according to the supposed structure of the Augustinian monastery (realized in the CVM Laboratory of the University of Pavia, courtesy of Virginio Cantoni, Director).